Introduction

We have talked about Hooke's Law some already, and used it for tensor notation exercises and examples. Hooke's Law describes linear material behavior. It is commonly used for isotropic materials (same behavior in all directions), but can also be extended to anisotropic materials. It is in fact the 1st order linearization of any hyperelastic material Law, including nonlinear ones. So it can be applied to rubber as long as the strains are small. And it is the standard for metals in the elastic range.Normal Components

The first step in getting to the full model is to start with simple uniaxial tension/compression. In this case, the relationship is\[ \sigma = E \, \epsilon \]

That's simple enough. It is linear because the stress and strain terms are all first-order. Keep in mind that \(E\) has units of stress just like \(\sigma\) because strain is unitless.

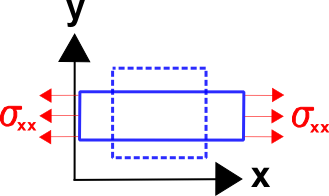

The next step is to generalize this for the case of multiple dimensions. For starters, decide that the tension/compression direction is \(x\). So the stress and strain in the above equation will be in the \(x\) direction. Also write the above equation a little differently as

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over E} \sigma_{xx} \]

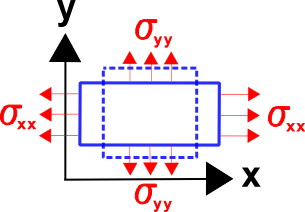

So far, so good. Now add some complexity. Add an additional normal stress in the \(y\) direction. Any tensile stress in the \(y\) direction will cause the strain in the \(x\) direction to decrease. So modify the above equation as follows.

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over E} \sigma_{xx} - B \, \sigma_{yy} \]

In this case, \(B\) is a material property just like \(E\) and requires a lab test to determine. Nevertheless, using \(B\) in this form is not very practical. It is much more useful to express \(B\) as a fraction of \((1 / E)\). Something like

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over E} \sigma_{xx} - f {1 \over E} \sigma_{yy} \]

where \(f\) is the "fraction". It is a number between 0 and 1 because material behavior dictates it to be so. It is less than 1 because strains in the \(x\) direction, \(\epsilon_{xx}\), are less sensitive to stresses in the \(y\) direction, \(\sigma_{yy}\), than they are to stresses in the \(x\) direction, \(\sigma_{xx}\).

Except that instead of using \(f\) as the symbol, use \(\nu\) instead. This is Poisson's ratio. It is the ratio of the sensitivity of strain to two stresses, one in line with the strain, and the other perpendicular to it.

We will see that Poisson's ratio is 1/2 for incompressible materials such as rubber. It is pretty consistently 1/3 for face-centered-cubic (FCC) materials like aluminum, nickel, and copper. And it is about 0.3 for steel.

So the above equation becomes

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{xx} - \nu \, \sigma_{yy} \big] \]

And now add in a \(\sigma_{zz}\) to the mix. If the material is isotropic, then the response of \(\epsilon_{xx}\) to \(\sigma_{zz}\) will be exactly the same as \(\sigma_{yy}\). So the equation can be written as

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{xx} - \nu \left( \sigma_{yy} + \sigma_{zz} \big) \right] \]

This is the complete Hooke's Law, at least for \(\epsilon_{xx}\). It is also the defining equation for Poisson's ratio (not \(-\epsilon_{yy} / \epsilon_{xx}\) by the way).

| POISSON RATIOS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Material | Poisson's Ratio | Comments |

| Foams | ~0 | Negligible effect |

| Steels | ~0.3 | Varies by a few % among steels |

| Aluminum | 0.33 | Face centered cubic (FCC) metals |

| Copper | 0.33 | |

| Nickel | 0.33 | |

| Rubber | 0.50 | Incompressible |

Hooke's Law Tension Example

How can you apply a tensile stress in the \(x\) direction, but still get a negative strain?Easy. Just apply sufficiently large tensile stresses in the \(y\) and \(z\) directions. Take Hooke's Law and declare it to be \(\le 0\).

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{xx} - \nu \left( \sigma_{yy} + \sigma_{zz} \big) \right] \le 0 \]

This leads to

\[ \sigma_{xx} \le \nu \left( \sigma_{yy} + \sigma_{zz} \right) \qquad \qquad (\text{gives } \epsilon_{xx} \le 0) \]

So the result does not depend on \(E\), but does depend on \(\nu\). If you pull hard enough in the \(y\) and \(z\) directions, you can produce negative strain in the \(x\) direction, even if \(\sigma_{xx} \ge 0\).

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{xx} - \nu \, ( \sigma_{yy} + \sigma_{zz} ) \big] \] \[ \epsilon_{yy} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{yy} - \nu \, ( \sigma_{xx} + \sigma_{zz} ) \big] \] \[ \epsilon_{zz} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{zz} - \nu \, ( \sigma_{xx} + \sigma_{yy} ) \big] \]

3-D Hooke's Law Example

For \(\sigma_{xx} = 2, \sigma_{yy} = 3, \sigma_{zz} = 4,\) and \(E = 10\), calculate the normal strains for three cases: \(\nu = 0\), \(\nu = 0.33\), and \(\nu = 0.5\).For \(\nu = 0.0\)...

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = 2 / 10 = 0.2 \] \[ \epsilon_{yy} = 3 / 10 = 0.3 \] \[ \epsilon_{zz} = 4 / 10 = 0.4 \]

For \(\nu = 0.33\)...

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over 10} \big[ 2 - 0.33 \, ( 3 + 4 ) \big] = -0.031 \] \[ \epsilon_{yy} = {1 \over 10} \big[ 3 - 0.33 \, ( 2 + 4 ) \big] = \;\;0.102 \] \[ \epsilon_{zz} = {1 \over 10} \big[ 4 - 0.33 \, ( 2 + 3 ) \big] = \;\;0.235 \]

For \(\nu = 0.5\)...

\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over 10} \big[ 2 - 0.5 \, ( 3 + 4 ) \big] = -0.15 \] \[ \epsilon_{yy} = {1 \over 10} \big[ 3 - 0.5 \, ( 2 + 4 ) \big] = \;\;0.00 \] \[ \epsilon_{zz} = {1 \over 10} \big[ 4 - 0.5 \, ( 2 + 3 ) \big] = \;\;0.15 \]

Life is relatively boring with \(\nu = 0\). The strains are directly proportional to the stresses. The remaining cases are much more interesting. There are two things to note. First, the resulting strain tensor is deviatoric when \(\nu = 0.5\). This will always be the case when \(\nu = 0.5\). Second, the \(\epsilon_{xx}\) term is negative even though \(\sigma_{xx}\) is positive. This is the often misunderstood Poisson effect.

Uniaxial Tension Example

If \(\sigma_{xx} = 2\), \(E = 10\), and \(\nu = 0.5\), then what is the resulting strain tensor.The resulting strains are \(\epsilon_{xx} = 0.2\), and \(\epsilon_{yy} = \epsilon_{zz} = -0.1\). So the strain tensor is

\[ \boldsymbol{\epsilon} = \left[ \matrix{ 0.2 & \;\;0.0 & \;\;0.0 \\ 0.0 & -0.1 & \;\;0.0 \\ 0.0 & \;\;0.0 & -0.1 } \right] \]

and the stress tensor is

\[ \boldsymbol{\sigma} = \left[ \matrix{ 2 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 } \right] \]

So you can get strains in directions that have no stress. This is another consequence of the Poisson effect.

Another important point to be made regarding Poisson's ratio is how it is equal to the ratios of \(\epsilon_{yy}\) and \(\epsilon_{zz}\) (the strains perpendicular to the loading direction) to \(\epsilon_{xx}\), the strain in the loading direction. This occurs for the case of uniaxial tension, and ONLY for uniaxial tension, not for all loading conditions. It is not a universal law or definition of Poisson's ratio.

Shear Components

We've worked out Hooke's Law for the normal components. We will now use them to develop the relationship between the shear stresses and strains. Start with a shear stress, \(\tau_{xy}\), and shear strain, \(\gamma_{xy}\), and rotate them 45° to get the principal values.\[ \left[ \matrix { 0 & \tau_{xy} \\ \tau_{xy} & 0 } \right] \qquad \matrix { 45^\circ \\ \text{transform} \\ \longrightarrow \; } \qquad \left[ \matrix { \tau_{xy} & 0 \\ 0 & -\tau_{xy} } \right] \]

and the shear strain

\[ \left[ \matrix { 0 & \gamma_{xy} / 2 \\ \gamma_{xy} / 2 & 0 } \right] \qquad \matrix { 45^\circ \\ \text{transform} \\ \longrightarrow \; } \qquad \left[ \matrix { \gamma_{xy} / 2 & 0 \\ 0 & -\gamma_{xy} / 2 } \right] \]

So the principal values are

\[ \sigma_1 = \tau_{xy} \qquad \qquad \sigma_2 = -\tau_{xy} \qquad \qquad \epsilon_1 = \gamma_{xy} / 2 \qquad \qquad \epsilon_2 = -\gamma_{xy} / 2 \]

Plugging the positive principal strain into Hooke's Law gives

\[ \epsilon_1 = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_1 - \nu \left( \sigma_2 + \sigma_3 \right) \big] \]

\[ {\gamma_{xy} \over 2} = {1 \over E} \big[ \tau_{xy} - \nu \left( -\tau_{xy} + 0 \right) \big] \]

Rearrange to get

\[ \tau_{xy} = {E \over 2 (1 + \nu) } \gamma_{xy} \]

And this leads to the expression for the shear modulus.

\[ G = {\tau_{xy} \over \gamma_{xy}} = {E \over 2 (1 + \nu) } \]

Shear Modulus

For rubber with \(\nu = 0.5\), the shear modulus, \(G\), will always be \(1/3\) of the tensile modulus, \(E\).\[ {G \over E} = {1 \over 3} \qquad \qquad \text{rubber} \]

For metals, especially the FCC ones, the Poisson ratio is \(\nu = 0.33\). This leads to the shear modulus being \(3/8\), or 37.5% of the tensile modulus.

\[ {G \over E} = {3 \over 8} \qquad \qquad \text{metals} \]

Bulk Modulus

Return to the three equations for normal strain in terms of normal stress.\[ \epsilon_{xx} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{xx} - \nu \, ( \sigma_{yy} + \sigma_{zz} ) \big] \] \[ \epsilon_{yy} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{yy} - \nu \, ( \sigma_{xx} + \sigma_{zz} ) \big] \] \[ \epsilon_{zz} = {1 \over E} \big[ \sigma_{zz} - \nu \, ( \sigma_{xx} + \sigma_{yy} ) \big] \]

Add the three equations together.

\[ \epsilon_{xx} + \epsilon_{yy} + \epsilon_{zz} = { (1 - 2 \nu) \over E} ( \sigma_{xx} + \sigma_{yy} + \sigma_{zz} ) \]

But \((\epsilon_{xx} + \epsilon_{yy} + \epsilon_{zz})\) is the volumetric strain, \(\epsilon_\text{Vol} = \Delta V / V\). We will discuss this at length in the next chapter on strain and deformations.

And \((\sigma_{xx} + \sigma_{yy} + \sigma_{zz})\) is three times the hydrostatic stress, \(3 \, \sigma_\text{Hyd}\). Note that hydrostatic stress is simply the average of the diagonal components and is the pressure your ears feel when you go deep under water.

So the equation becomes

\[ \epsilon_\text{Vol} = { 3 (1 - 2 \nu) \over E} \sigma_\text{Hyd} \]

And the ratio of the \(\sigma_\text{Hyd}\) to \(\epsilon_\text{Vol}\) is the bulk modulus, \(K\).

\[ K = { \sigma_\text{Hyd} \over \epsilon_\text{Vol} } = { E \over 3 (1 - 2 \nu) } \]

And a little more rearrangement gives

\[ {E \over K} = 3 (1 - 2 \nu) \]

This is the important relationship between tensile modulus and bulk modulus. Although the bulk modulus for rubber is not large, it is nevertheless much larger than the tensile modulus. So the ratio of the two is very small. This dictates that the Poisson Ratio for rubber must be 0.5. This is so that the RHS term, \(3 ( 1 - 2 \nu )\), equals zero.

Bulk Modulus

For steel, its elastic modulus is 200,000 MPa and Poisson's Ratio is 0.30. Its bulk modulus is\[ K \; = \; { E \over 3 (1 - 2 \nu) } \; = \; { 200,000 \over 3 (1 - 2*0.30 ) } \; = \; 167,000 \text{ MPa} \]

For aluminum, its elastic modulus is 70,000 MPa and Poisson's Ratio is 0.33. Its bulk modulus turns out to be the same value as the elastic modulus.

\[ K \; = \; { E \over 3 (1 - 2 \nu) } \; = \; { 70,000 \over 3 (1 - 2*0.33 ) } \; = \; 70,000 \text{ MPa} \]

For the case of rubber, its bulk modulus is on the order of 1,000 MPa. This is clearly much lower than steel or aluminum, so rubber is actually much more compressible than the metals. Nevertheless, it is considered incompressible because its bulk modulus is still several orders of magnitude greater than its tensile and shear moduli.

Matrix & Tensor Notation

\[ \boldsymbol{\epsilon} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \boldsymbol{\sigma} - \nu \; {\bf I} \; \text{tr}(\boldsymbol{\sigma}) \right] \]

and in tensor notation as

\[ \epsilon_{ij} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{ij} - \nu \; \delta_{ij} \; \sigma_{kk} \right] \]

Writing all the matrices out gives

\[ \left[ \matrix { \epsilon_{11} & \epsilon_{12} & \epsilon_{13} \\ \epsilon_{21} & \epsilon_{22} & \epsilon_{23} \\ \epsilon_{31} & \epsilon_{32} & \epsilon_{33} } \right] = {1 \over E} \left\{ (1 + \nu) \left[ \matrix { \sigma_{11} & \sigma_{12} & \sigma_{13} \\ \sigma_{21} & \sigma_{22} & \sigma_{23} \\ \sigma_{31} & \sigma_{32} & \sigma_{33} } \right] - \nu \, ( \sigma_{11} + \sigma_{22} + \sigma_{33} ) \left[ \matrix { 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1} \right] \right\} \]

The individual component equations all together are

\[ \epsilon_{11} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{11} - \nu \; (\sigma_{11} + \sigma_{22} + \sigma_{33}) \right] \qquad \qquad \epsilon_{12} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{12} \right] \] \[ \epsilon_{22} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{22} - \nu \; (\sigma_{11} + \sigma_{22} + \sigma_{33}) \right] \qquad \qquad \epsilon_{13} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{13} \right] \] \[ \epsilon_{33} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{33} - \nu \; (\sigma_{11} + \sigma_{22} + \sigma_{33}) \right] \qquad \qquad \epsilon_{23} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{23} \right] \]

but then clean up into the familiar forms

\[ \epsilon_{11} = {1 \over E} \left[ \sigma_{11} - \nu \; (\sigma_{22} + \sigma_{33}) \right] \qquad \qquad \epsilon_{12} = {(1 + \nu) \over E} \sigma_{12} \] \[ \epsilon_{22} = {1 \over E} \left[ \sigma_{22} - \nu \; (\sigma_{11} + \sigma_{33}) \right] \qquad \qquad \epsilon_{13} = {(1 + \nu) \over E} \sigma_{13} \] \[ \epsilon_{33} = {1 \over E} \left[ \sigma_{33} - \nu \; (\sigma_{11} + \sigma_{22}) \right] \qquad \qquad \epsilon_{23} = {(1 + \nu) \over E} \sigma_{23} \]

For anyone diving directly into this page here, note that \(\epsilon_{12}\), \(\epsilon_{13}\), and \(\epsilon_{23}\) are one-half of the normal shear quantities, i.e., \(\epsilon_{12} = \gamma_{12} / 2\).

Inverting Hooke's Law

This will demonstrate how to invert Hooke's Law from strain-as-a-function-of-stress to stress-as-a-function-of-strain.Returning to the fundamental equation...

\[ \epsilon_{ij} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{ij} - \nu \; \delta_{ij} \; \sigma_{kk} \right] \]

It is easy to solve for \(\sigma_{ij}\) to get

\[ \sigma_{ij} = {1 \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ E \; \epsilon_{ij} + \nu \; \delta_{ij} \; \sigma_{kk} \right] \]

Multiply both sides by \(\delta_{ij}\)

\[ \delta_{ij} \sigma_{ij} = {1 \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ E \; \delta_{ij} \; \epsilon_{ij} + \nu \; \delta_{ij} \; \delta_{ij} \; \sigma_{kk} \right] \]

and simplify

\[ \sigma_{kk} = {E \; \epsilon_{jj} \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \]

\[ \sigma_{ij} = {1 \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ E \; \epsilon_{ij} + \nu \; \delta_{ij} \; \sigma_{kk} \right] \]

to obtain

\[ \sigma_{ij} = {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ \epsilon_{ij} + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \epsilon_{kk} \right] \]

Note that in this equation, it is impossible to calculate the stress tensor given a strain tensor if the material is incompressible because \(\nu = 0.5\).

Stiffness Tensor

The stiffness tensor is a 4th rank quantity (3x3x3x3) that relates stress to strain.\[ \boldsymbol{\sigma} = {\bf C} : \boldsymbol{\epsilon} \qquad \qquad \sigma_{ij} = C_{ijkl} \epsilon_{kl} \]

We will see on the thermodynamics page that the stiffness tensor is fundamentally the second partial derivative of the Helmholtz free energy with respect to the elastic portion of the Green strain tensor.

\[ {\bf C} = \rho_o \, {\partial^2 \Psi \over \partial \boldsymbol{\epsilon}^\text{el} \partial \boldsymbol{\epsilon}^\text{el} } \]

But alas, this is not very useful when doing most analyses. Instead, it is much easier to take the derivative of Hooke's Law. Start by writing Hooke's Law in tensor notation.

\[ \sigma_{ij} = {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ \epsilon_{ij} + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \epsilon_{mm} \right] \]

And take the derivative as follows.

\[ \begin{eqnarray} C_{ijkl} & = & {\partial \sigma_{ij} \over \partial \epsilon_{kl} } \\ \\ \\ & = & {\partial \over \partial \epsilon_{kl} } \left\{ {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ \epsilon_{ij} + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \epsilon_{mm} \right] \right\} \\ \\ \\ & = & {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ \delta_{ik} \, \delta_{jl} + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \delta_{mk} \, \delta_{ml} \right] \end{eqnarray} \]

The Kronecker deltas appear because

\[ {\partial \epsilon_{ij} \over \partial \epsilon_{kl} } = \delta_{ik} \, \delta_{jl} \qquad \qquad \text{and} \qquad \qquad {\partial \epsilon_{mm} \over \partial \epsilon_{kl} } = \delta_{mk} \, \delta_{ml} \]

Except... all this is wrong!!! WRONG, WRONG, WRONG!!!

The problem is that the equation for the stiffness tensor is not symmetric with respect to \(i\) and \(j\), as \(\sigma_{ij}\) is, and with respect to \(k\) and \(l\), as \(\epsilon_{kl}\) is.

You can see this by looking at the first term above, \(\delta_{ik} \, \delta_{jl}\). This term is not symmetric with respect to \(i\) and \(j\) because swapping them gives \(\delta_{jk} \, \delta_{il}\), which is a different, and therefore not symmetric result.

The problem is way back with the original Hooke's Law equation.

\[ \sigma_{ij} = {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ \epsilon_{ij} + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \epsilon_{mm} \right] \]

The issue here is that this equation does not force the tensors to be symmetric. The stress and strain tensors could easily be nonsymmetric and still satisfy Hooke's Law. So before taking the derivative with respect to strain, the equation can be modified to force symmetry. This is accomplished by replacing \(\epsilon_{ij}\) with

\[ \epsilon_{ij} \; \rightarrow \; { \epsilon_{ij} + \epsilon_{ji} \over 2 } \]

So Hooke's Law becomes

\[ \sigma_{ij} = {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ { 1 \over 2} (\epsilon_{ij} + \epsilon_{ji}) + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \epsilon_{mm} \right] \]

This equation forces the stress tensor to be symmetric. Now taking the derivative of this gives

\[ \begin{eqnarray} C_{ijkl} & = & {\partial \sigma_{ij} \over \partial \epsilon_{kl} } \\ \\ \\ & = & {\partial \over \partial \epsilon_{kl} } \left\{ {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ { 1 \over 2} (\epsilon_{ij} + \epsilon_{ji}) + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \epsilon_{mm} \right] \right\} \\ \\ \\ & = & {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ {1 \over 2} ( \delta_{ik} \, \delta_{jl} + \delta_{jk} \, \delta_{il} ) + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \delta_{mk} \, \delta_{ml} \right] \\ \\ \\ & = & {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ {1 \over 2} ( \delta_{ik} \, \delta_{jl} + \delta_{jk} \, \delta_{il} ) + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \delta_{kl} \right] \end{eqnarray} \]

This is now symmetric with respect to \(i\) and \(j\) and with respect to \(k\) and \(l\).

Stiffness Tensor Example

Start with\[ C_{ijkl} = {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ {1 \over 2} ( \delta_{ik} \, \delta_{jl} + \delta_{jk} \, \delta_{il} ) + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{ij} \, \delta_{kl} \right] \]

And determine \(C_{1111}\), the coefficient of \(\epsilon_{11}\) that contributes to \(\sigma_{11}\).

\[ \begin{eqnarray} C_{1111} & = & {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ {1 \over 2} ( \delta_{11} \, \delta_{11} + \delta_{11} \, \delta_{11} ) + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \delta_{11} \, \delta_{11} \right] \\ \\ \\ & = & {E \over (1 + \nu)} \left[ 1 + { \nu \over (1 - 2 \nu)} \right] \\ \\ \\ & = & {E \, ( 1 - \nu) \over (1 + \nu) (1 - 2 \nu) } \end{eqnarray} \]

Keep in mind that \(C_{1111}\) is \({\partial \sigma_{11} \over \partial \epsilon_{11}}\), and this implies that \(\epsilon_{22}\) and \(\epsilon_{33}\) are held constant while \(\epsilon_{11}\) changes.

Once again, the consequence of this scenario is that the volume does change. That is why \(C_{1111}\) has \(1-2\nu\) in the denominator and goes to \(\infty\) as \(\nu\) approaches 0.5, because the material approaches incompressibility and requires an infinite amount of stress to change its volume.

Also, note that \(C_{1111}\) is not the material's stiffness under uniaxial tension because, in that case, the lateral strains do indeed change due to Poisson's effect, so they are not constant as the partial derivative implies.

Deviatoric Stress & Strain

This section develops a fascinating relationship between deviatoric stress and strain based on Hooke's Law. Start with the usual relationship.\[ \epsilon_{ij} = {1 \over E} \left[ (1 + \nu) \sigma_{ij} - \nu \, \delta_{ij} \sigma_{kk} \right] \]

\[ \epsilon_{kk} = { (1 - 2 \nu) \over E} \sigma_{kk} \]

And then multiply both sides by \({ 1 \over 3} \delta_{ij}\) again to get

\[ { 1 \over 3} \delta_{ij} \epsilon_{kk} = {(1 - 2 \nu) \over 3 E} \delta_{ij} \sigma_{kk} \]

This results in an equation relating the hydrostatic stress and strain values.

Now subtract it from the original Hooke's Law equation to get

\[ \begin{eqnarray} \epsilon_{ij} - { 1 \over 3} \delta_{ij} \epsilon_{kk} & \, = \, & { (1 + \nu) \over E} \sigma_{ij} - { \nu \over E} \, \delta_{ij} \sigma_{kk} - {(1 - 2 \nu) \over 3 E} \delta_{ij} \sigma_{kk} \\ \\ \\ & \, = \, & { (1 + \nu) \over E} \sigma_{ij} - { 1 \over E} \left( \nu + {1 - 2 \nu \over 3} \right) \delta_{ij} \sigma_{kk} \\ \\ \\ & \, = \, & { (1 + \nu) \over E} \sigma_{ij} - { 1 \over 3} {(1 + \nu) \over E} \delta_{ij} \sigma_{kk} \\ \\ \\ & \, = \, & { (1 + \nu) \over E} \big( \sigma_{ij} - { 1 \over 3} \delta_{ij} \sigma_{kk} \big) \\ \end{eqnarray} \]

The remarkable result is that both sides of the equation contain a deviatoric tensor result. The equation can be summarized as

\[ \epsilon'\!_{ij} = { ( 1 + \nu ) \over E} \sigma'\!_{ij} \]

But \({ (1 + \nu) \over E }\) is \({1 \over 2G}\), so the equation can be further simplified to

\[ \epsilon'\!_{ij} = { 1 \over 2 G} \sigma'\!_{ij} \]

So the deviatoric stress and strain are directly proportional to each other. The amazing thing here is that this is always true for Hooke's Law, always, even for the normal strain components.

For what it's worth, the equation can also be written as

\[ \sigma'\!_{ij} = 2 \, G \, \epsilon'\!_{ij} \]

Deviatoric Example with Hooke's Law

Suppose you have a BT material with Poisson's ratio, \(\nu = 0.5\), and elastic modulus, \(E = 15\;MPa\).For the stress tensor below, use Hooke's Law to calculate the strain state. Then get the deviatoric stress and strain tensors and show that they are proportional to each other by the factor \(2G\).

\[ \boldsymbol{\sigma} \; = \; \left[ \matrix{ 8 & 2 & 4 \\ 2 & 6 & 6 \\ 4 & 6 & 4 } \right] \]

Note that this stress tensor clearly has a significant amount of hydrostatic stress. It is

\[ \boldsymbol{\sigma}_\text{Hyd} \; = \; \left[ \matrix{ 6 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 6 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 6 } \right] \]

Hooke's Law is

\[ \begin{eqnarray} \left[ \matrix{ \epsilon_{xx} & \epsilon_{xy} & \epsilon_{xz} \\ \epsilon_{xy} & \epsilon_{yy} & \epsilon_{yz} \\ \epsilon_{xz} & \epsilon_{yz} & \epsilon_{zz} } \right] & = & {1 \over 15} \left\{ (1 + 0.5) \left[ \matrix{ 8 & 2 & 4 \\ 2 & 6 & 6 \\ 4 & 6 & 4 } \right] - 3 \; (0.5) \left[ \matrix { 6 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 6 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 6 } \right] \right\} \\ \\ \\ \\ & = & {1 \over 15} \left\{ \left[ \matrix{ 12 & 3 & 6 \\ 3 & 9 & 9 \\ 6 & 9 & 6 } \right] - \left[ \matrix{ 9 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 9 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 9 } \right] \right\} \\ \\ \\ \\ & = & \left[ \matrix{ 0.2 & \;0.2 & \;0.4 \\ 0.2 & \;0.0 & \;0.6 \\ 0.4 & \;0.6 & \text{-}0.2 } \right] \end{eqnarray} \]

Note that this strain tensor is already deviatoric. This is because we used \(\nu = 0.5\) for the Poisson's Ratio, which is the value used for incompressible materials. So we obtained an incompressible, non-hydrostatic strain tensor as a result.

So the question becomes, "Will (\(2 \, G \, \boldsymbol{\epsilon}'\)) give \(\boldsymbol{\sigma}'\)?"

To answer this, first compute \(G\).

\[ \begin{eqnarray} G & = & {E \over 2 ( 1 + \nu) } & = & {15 \text{ MPa} \over 2 ( 1 + 0.5) } \\ \\ & = & 5 \text{ MPa} \end{eqnarray} \]

So \(2 \, G \, \boldsymbol{\epsilon}'\) equals

\[ 2 \, G \, \boldsymbol{\epsilon}' = \left[ \matrix{ 2 & \;2 & \;4 \\ 2 & \;0 & \;6 \\ 4 & \;6 & \text{-}2 } \right] \]

And compare this to \(\boldsymbol{\sigma} - \boldsymbol{\sigma}_\text{Hyd}\)

\[ \left[ \matrix{ 8 & 2 & 4 \\ 2 & 6 & 6 \\ 4 & 6 & 4 } \right] - \left[ \matrix { 6 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 6 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 6 } \right] = \left[ \matrix { 2 & \;2 & \;4 \\ 2 & \;0 & \;6 \\ 4 & \;6 & \text{-}2 } \right] \]

So it does indeed satisfy \(\boldsymbol{\sigma}' = 2 \, G \, \boldsymbol{\epsilon}'\). Although this was an example with an incompressible material, \(\nu = 0.5\), it also works for compressible materials as well, always.